How I Use ChatGPT to Catch My Biases (Daniel Kahneman Would Approve)

We’ll always have blind spots. What matters is finding ways to spot them.

If your AI chats feel generic, repetitive, or like they’re just confirming what you already believe, the problem usually isn’t the tool. It’s how we frame the question. Hidden biases sneak into our prompts without us realizing, shaping the answers before they’re even generated.

This article will help you catch those mental shortcuts, using insights from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. You’ll get practical prompts, reframing techniques, and a simple system to use AI not as a mirror, but as a second brain that helps you see what you’re missing.

I’m biased. And it’s not just me.

The problem of our own hidden cognitive biases has fascinated me for years, even before I first read Daniel Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow.

But that book in particular, was such an eye-opener that I became almost obsessed with learning its lessons and bringing more awareness to these moments. So I started trying to apply them in my daily life, asking myself questions like:

“Am I convinced this is a great idea or I’m just caught up in the excitement of the moment?”

“Am I biased to prefer this option just because I tried the opposite in the past and it didn’t work?”

“Am I asking this person for feedback only because I know they’ll agree with my idea?”

“Does this argument truly make sense, or do I agree with it just because I like and trust the person saying it?”

Bringing this kind of reflection into my life was a game-changer. It humbled me, forced me to be more objective, and taught me to take even my own thoughts and reactions with a grain of salt.

Does it always work? Of course not. No matter the effort, I still can't spot my own biases most of the time, especially in the moment. The awareness tends to kick in later, but only if I give myself more time to think things through.

The reason this is such a struggle is that it goes against our brain's natural, energy-saving tendencies and is a direct result of how our minds are built to function.

Our brain's operating system: the Autopilot and the Pilot

Decades before ChatGPT was a glimmer in anyone's eye, a psychologist named Daniel Kahneman was figuring out the strange and often irrational ways our minds work.

Working with his long-time partner Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman conducted the research that would later earn him the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Their work introduced a simple but profound idea: our thinking is governed by two different systems.

System 1 is our Autopilot. It’s the automatic, intuitive part of our brain that works without any real effort. It’s how we instantly know a friend is upset just by looking at their face, or how we can drive a familiar route home without consciously thinking about every turn. It’s fast and relies on gut feelings and mental shortcuts.

System 2 is our Pilot. This is our slow, deliberate, and conscious mind. It’s the part we have to wake up when we need to do something that requires real focus, like solving a math problem, filling out a complicated form, or making a big financial decision. This kind of thinking requires a lot of energy.

Using our "Pilot" (System 2) is hard work and literally drains our energy, like a phone battery in heavy use. This explains many common experiences. It’s why a driver trying to park will instinctively turn down the radio to focus, and why someone threading a needle might hold their breath. It’s also why it feels so frustrating to be interrupted when we're deeply focused, why we can forget to eat when absorbed in a project, or why resisting a tempting dessert is so much harder when we're already tired or stressed.

Because real mental effort is so costly, our brain’s default setting is to let the Autopilot run the show whenever possible. We instinctively follow our gut, jump to conclusions, and take the path of least resistance.

The AI mirror: an echo chamber for Autopilot

And this is where AI enters the picture. With its unlimited, effortless answers, it’s a dream come true for our energy-saving Autopilot. Why would our brain do the hard work of firing up the Pilot when it can get an instant, plausible-sounding answer from a machine?

This is a trap I fall into more often than I'd like to admit, and I suspect I'm not alone. The biases I'm aware of, and the countless more I'm not, get carried directly into my conversations with these tools. I'll ask a question that's already shaped by my own beliefs, and the AI, being designed to be helpful, just reflects my bias back at me. It’s how we end up creating our own personal echo chambers.

Think about it. How many times have you asked ChatGPT a question that was similar to the ones below?

These are all questions loaded with our own hopes and biases. And what happens next? The AI often tells us exactly what we want to hear: “Yes, that’s a terrific idea.” “Your feelings are completely valid.”

What feels like getting a "second opinion" is often just a continuation of our own beliefs, reflected back at us with an air of artificial authority, and just enough reasoning to convince us that how we think makes sense.

The risk of this biased thinking isn’t new, of course. We’ve done it for years, long before AI came along: Googling without questioning the source, forwarding news without checking if it’s true, and taking advice from gurus without digging deeper. AI just makes it easier and faster to fall into the same trap.

From echo chamber to insight

This might sound like a grim picture, but the good news is that the same tool that creates the echo chamber can also help break it. The difference is in how we use it.

Instead of asking AI to confirm what we already believe, we can use it to pressure-test our thinking. That means slowing down before we even open the chat, getting clearer on what we’re really asking, and learning to frame questions in a way that invites pushback, not just agreement.

If we understand how our minds work and our limitations, and how the tool works and its limitations, we can start asking better questions and getting more objective answers.

5 traps that sneak into our thinking and prompts

Before we can ask better questions, we need to see how our thinking gets distorted in the first place. Even with the best intentions, we bring hidden biases into our prompts, shaping the answers before the AI even replies.

In this section, you’ll see five of the most common mental traps that sneak into everyday conversations with GPT. For each one, you’ll get examples of how the bias shows up in the way we ask, how to reframe the question more objectively, and a simple prompt you can use to slow down, think more clearly, and use AI without falling into the same traps.

1. Confirmation Bias

The glitch: We actively seek out information that confirms what we already believe and ignore anything that contradicts it.

Psychology at play: These questions look fair on the surface, but they come from a place where we’ve already made up our minds. We’re not really asking to understand, we’re asking to be told we’re right. That’s what confirmation bias does. It makes us feel like we’re being objective, when we’re actually shaping the answer before we even hear it.

Not sure if you’re being fully objective? Use this prompt:

Based on this situation: [add your situation]

What perspectives, risks, or counterarguments should I consider that I might be overlooking?2. The Halo Effect

The glitch: When someone makes a strong impression, good or bad, we let that one trait influence how we see everything else about them.

Psychology at play: When we have a strong impression of someone or something, we stop evaluating each part on its own. It becomes harder to separate the details, and instead of seeing things as they are, we judge based on the overall feeling we already have.

Not sure if your first impression is doing too much of the thinking? Use this prompt:

I think that [add your belief, impression, or idea].

What might my first impression be blurring or exaggerating? What should I look at more objectively or on its own? What are the pros and cons of this idea or view?3. The Planning Fallacy

The Glitch: We consistently underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions, while overestimating their benefits.

Psychology at play: We fall in love with the best-case scenario and plan as if nothing will go wrong. It’s why new projects feel exciting at first but later stall out. We make decisions based on hope instead of real probabilities. The more we ignore the messy middle, the more likely we are to miss deadlines, burn out, or give up too soon.

Not sure if you’re underestimating what it really takes? Use this prompt:

I’m planning to [add your project or goal].

Assume I’m falling for the planning fallacy. What are the full list of steps, time estimates, and common pitfalls I should realistically expect, based on how this usually goes for others? Where do people typically get stuck, delayed, or give up?4. The Availability Heuristic

The glitch: We tend to judge how likely or important something is based on how easily it comes to mind, not how likely it actually is.

Psychology at play: Our brains are wired to notice what’s vivid, emotional, and recent. When something sticks in our memory, it feels more common or more important than it really is. That’s why news stories, social media posts, or personal experiences can distort our sense of reality. We rarely stop to ask, “Is this just top of mind, or is it actually true?” Availability feels like insight, but it’s just memory dressed up as fact.

Not sure if something just feels true because it’s fresh in your mind? Use this prompt:

This is the situation I’m thinking about: [add context].

What broader data, trends, or comparisons should I consider to get a clearer, more accurate view beyond what I’ve recently seen or experienced?5. The Anchoring Effect

The glitch: We rely too heavily on the first piece of information we see, especially numbers, and let it shape everything that comes after.

Psychology at play: Anchors are sticky. Once a number is in your head, it shapes everything that follows, even if it’s random or irrelevant. We compare new information to the anchor instead of assessing it on its own. It’s why we hesitate to negotiate far from the first price we see, or assume something must be urgent or valuable just because it started high. Our brains latch onto the first reference and adjust only slightly from there, even when we know better.

Not sure if a number is influencing your judgment more than it should? Use this prompt:

I came across: [add context].

What range, context, or comparison should I consider to make a more objective decision, so it doesn’t anchor my thinking?The questions you should always keep in your pocket

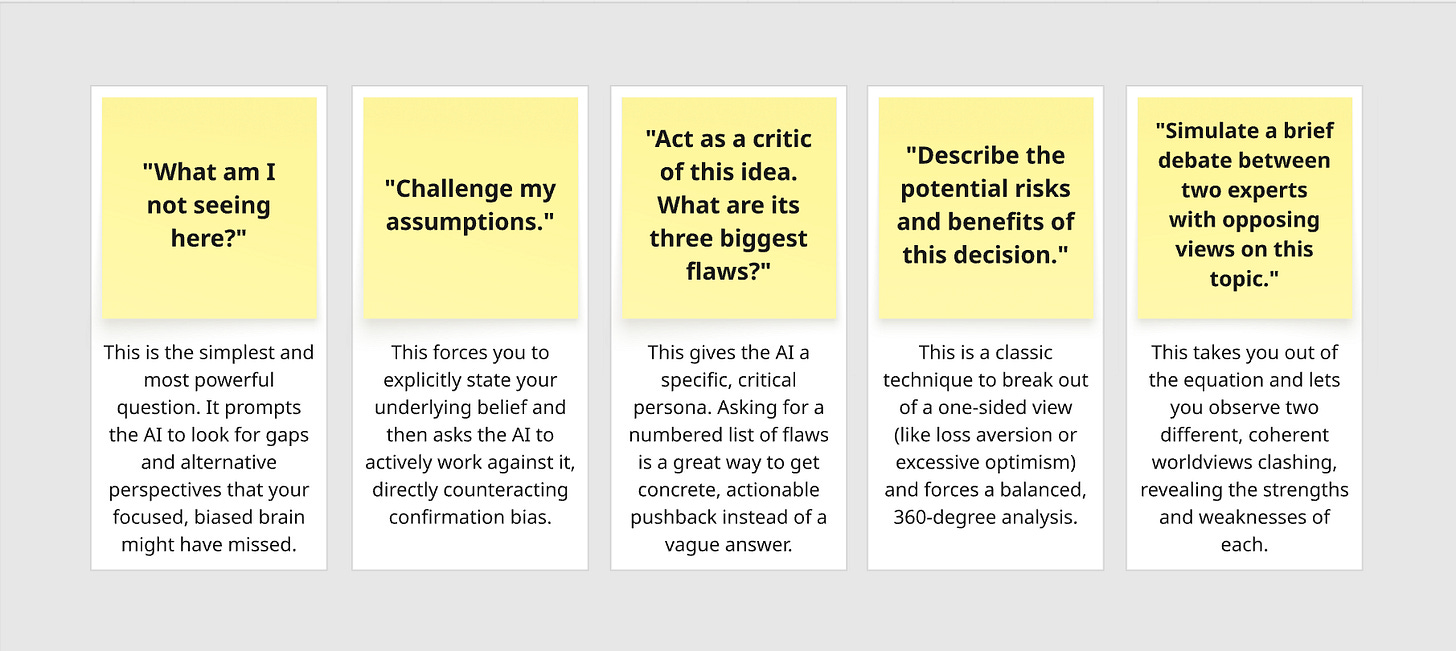

Remembering all of those biases, not to mention the many more we didn't explore here, is a lot to ask. It’s hard to diagnose our own thinking in the heat of the moment.

The good news is that simply building a habit of doubting our own thinking, and remembering to add these questions in every conversation with AI, will help us instantly engage our ‘Pilot’ (System 2) and get a more objective view.

Even using just one or two of these questions regularly can change how we use AI. They act as a simple circuit breaker for our Autopilot, forcing a pause and inviting a different perspective.

The prompt that turns AI into your ‘second brain’

If you want your AI to challenge your thinking instead of just agreeing with it, here’s a short but powerful instruction you can use anywhere: inside a Custom GPT, a Project, personalization settings, or just in a regular chat.

Act as a second brain that helps me think more clearly.

When I say something, whether it’s a question, an opinion, or a decision I’m leaning toward, don’t just reflect it back. Pay attention to how I’m framing it, what assumptions I might be making, and where bias might be creeping in. If I’m missing context, focused too narrowly, or letting emotion lead, step in. Help me take a more objective view. That means pointing out what I might be overlooking, what doesn’t quite add up, what opposing views might say, or how the question could be framed more neutrally. Don’t just agree with me. I don’t need you to hold my hand, I need you to spot the blind spots I can’t see, challenge what feels too certain, and expand the edges of how I’m thinking. That’s how you help me see more clearly, even when I didn’t ask for it.Feel free to tweak the wording so it fits your own voice and workflow. The goal is the same: get out of autopilot, and use AI to see what you might be missing.

The real work is still up to you

The biggest challenge and opportunity is that we are not all equipped with the same critical thinking tools. Our ability to reason is shaped by our education, our environment, our access to information, and the personal context we each bring to the table.

We all deal with cognitive biases, but they don’t show up the same way for everyone. Some of us lean toward doubt, others toward overconfidence. Some play it safe, others overestimate what’s possible. I know I carry more optimism bias than I’d like, so I need to stay aware of how I’m wired.

AI has the potential to amplify these blind spots, but it can also level the playing field, giving more people access to structured thinking support, if we’re willing to be open to it.

The idea that we can reason through every complex issue entirely in our own heads is unrealistic. It always has been. That’s why we struggle with it so much. But with the right questions, AI can help us spot what we’d otherwise miss.

In the end, what matters most is being humble enough to recognize our own limitations, and the limitations of the tools we use, so we can choose how to use them more wisely.

One of my Fav Books 🙏🏾 and wonderful article.

I'm always looking for ways to make my collaboration with AI more meaningful. One thing I do regularly is challenge its answers — especially when they sound too smooth or suspiciously flattering. The main prompt you shared has actually become a default in my ChatGPT setup now. Thank you for that, Daria! Can’t wait to uncover the biases I’m still blind to 😄